THE HUMBLE GENIUS

Georg Neumann

THE FACT THAT ONE DAY A HALL IN THE VENERABLE JAZZ INSTITUTE BERLIN WOULD BE NAMED AFTER HIM: NO, GEORG NEUMANN WOULDN’T HAVE WANTED THAT DURING HIS LIFETIME. EVEN WHEN HE HAD LONG BEEN ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT PERSONALITIES IN MICROPHONE MANUFACTURING, AND HIS IDEAS AND PRODUCTS WERE MET WITH ENTHUSIASM ALL OVER THE WORLD, THE SILENT INVENTOR ALWAYS REMAINED MODEST AND PREFERRED TO STAY IN THE BACKGROUND.

So who was the man whose innovations accompanied — and still accompany — entire generations of sound engineers and musicians? An anecdote that wonderfully describes Georg Neumann goes like this: After the war, his son Ralph finds a rechargeable battery pack with two cells, one of which was damaged. “My father really wanted the battery pack. Finally, he made a suggestion: ‘I’ll just take the damaged cell; you can keep the one that’s intact.’” Cautiousness and reservation on the one hand, and curiosity and inventive talent on the other: that’s what made Neumann’s character so special. The defective cell, by the way, marked the beginning of his thoughts on gas-tight manufacture of nickel-cadmium batteries — a technological milestone.

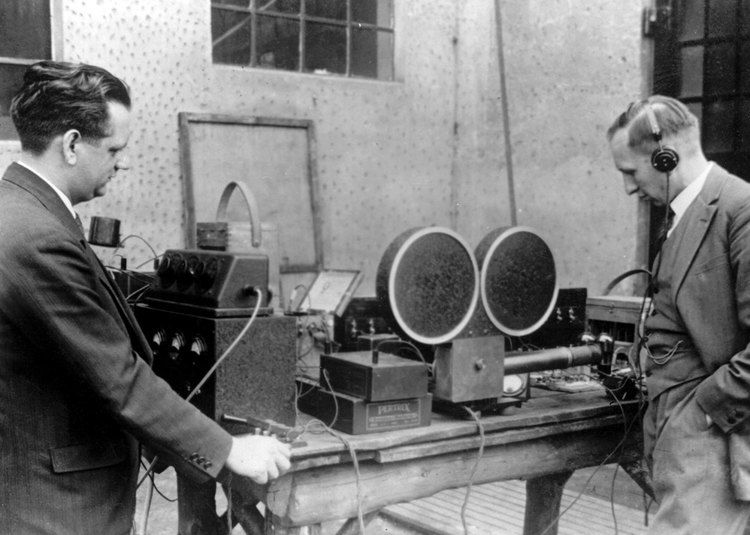

Georg Neumann (left) in the laboratory with Erich Kühnast, a longtime employee of the formerly called Georg Neumann & Co.

This passion to not only overcome technical hurdles but also to go fundamentally new ways runs through his entire life. From the groundbreaking Reisz microphone to high-precision electroacoustic measuring instruments and pioneering record-cutting technology through to the Stabylit cell — Georg Neumann’s ingenuity knew no boundaries. Whatever interested him, whatever stimulated his ambition, he would take on. In silence, preferably in his own laboratory, he regularly pushed the boundaries of what was technologically feasible.

His creations not only changed an entire industry in a lasting manner but also paid off for his company: Neumann thrived in the 50s and 60s, and the employees were highly motivated. Their boss had a quiet management style: gentle steering from the background, offering targeted suggestions on how to solve problems: “Do it this way or that or just use some other material,” former employees remember. He was attentive, liked to make his employees happy, and always had an open ear — especially for technical problems. The working atmosphere was so good that many people spent their entire working life at Neumann; the ten years they had been with the company were also jokingly celebrated as having passed the probationary period.

Neumann could have been more than proud of himself because of his great success, but “he was far too modest for that,” says his daughter Ingrid. One of the few hobbies he granted himself was water sports. He met his later wife Elly at the boat club; with her open, vivacious manner, she became a window to the world for the quiet Neumann as well as his closest confidante. Family harmony became an important foundation for the work of the ingenious inventor.

Georg Neumann changed the electroacoustics of his era so fundamentally — perhaps he would find it modest to name only a small hall after him.

Georg Neumann (center) receives the Emil Berliner Award, left: Peter Burkowitz (Deutsche Grammophon), right: Günter Lützkendorf (Neumann’s managing director at the time)